Life at 2812 Monument Avenue in 1918

When the Seminole Apartments opened their doors in 1918, Richmond was in the midst of transformation. The trolley lines ran steady along the Boulevard, automobiles shared the streets with horse-drawn wagons, and the city’s skyline was stretching westward beyond the traditional bounds of downtown. Amid this new era of movement and modern convenience, the Davis Brothers introduced something novel to Monument Avenue — a form of living that blended the independence of a private home with the sophistication and practicality of city apartment life.

A Modern Monument Avenue Residence

Designed and built by the prolific Davis Brothers, the Seminole Apartments at 2812 Monument Avenue reflected their signature balance of modest elegance and structural integrity. The façade — brick trimmed with classical details — presented a sense of refinement without ostentation. Behind it, the building unfolded into a series of efficiently planned flats arranged for privacy and light.

Each unit opened from a shared corridor into a gracious front parlor, typically facing Monument Avenue’s grand tree-lined median. Tall windows and French doors allowed abundant daylight and natural ventilation — a prized feature in an age before air conditioning. From these front rooms, a progression of spaces led back toward the kitchen and service areas, revealing much about how residents lived and how domestic routines were changing.

The Apartment Layout and Daily Rhythm

The blueprints show a symmetrical structure, with paired apartments on each floor mirroring one another along a central hallway. Each flat contained a front parlor, a formal dining room, two to three bedrooms, a bathroom, and a rear kitchen connected to a small porch or service stair. The kitchens were compact but efficient — built for daily cooking rather than elaborate entertaining. A coal or gas range, a single porcelain sink, and built-in cabinetry lined one wall.

Most apartments were designed with rear service corridors or stairways, enabling deliveries and the discreet movement of domestic staff. While not every tenant employed a full-time maid, many middle-class residents hired part-time help who cooked, cleaned, or laundered once or twice a week. Maids typically entered through the rear service door, kept to the kitchen, and left by evening — a holdover from the servant culture of the late Victorian era, now evolving to match the more independent rhythms of modern life.

Who Lived at the Seminole

The residents of 2812 Monument Avenue were part of Richmond’s new professional middle class. They were teachers, clerks, bank officers, small business owners, and young couples seeking comfort and status without the upkeep of a house. Apartments like the Seminole offered them the prestige of a Monument Avenue address at a fraction of the cost of owning a single-family home.

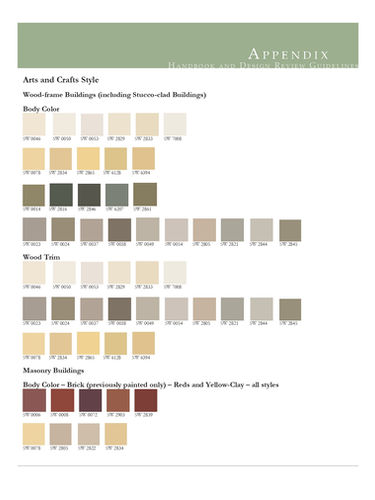

It wasn’t uncommon for widows or older couples to occupy one unit, while newly married professionals rented another. The building’s proximity to the streetcar line and downtown made it ideal for office workers and government employees. Most residents furnished their apartments with Mission or Colonial Revival furniture — stylish but sensible pieces that reflected the Craftsman influence in both architecture and lifestyle.

Community and Operation

The Seminole functioned as a self-contained urban residence. There was no grand lobby as in later luxury buildings; instead, the entry hall was understated, leading directly to the stairwell and corridors. Heat was provided by a central boiler in the basement, feeding radiators in each unit — a major convenience in 1918.

Mailboxes and call bells near the entryway connected residents to the building manager, who likely lived on-site or nearby. Laundry was hung on the rear porches, and deliveries — groceries, ice, or coal — came to the back entrance via narrow alleys. Tenants knew their neighbors by sight, if not by name, and polite social contact was common — a nod on the staircase, shared conversation on the front porch, or the occasional invitation for tea in the parlor.

There were no shared dining halls or communal kitchens, as these apartments were designed for private domestic life. However, the proximity of service rooms and the uniform layout allowed for efficient maintenance. Building staff — typically one custodian or janitor — kept the furnace stoked and the stairways clean. In many ways, life at the Seminole balanced independence with quiet community — urban living without the impersonality of a hotel.

An Architecture of Transition

The Seminole embodied the transitional moment between the grand homes of the Gilded Age and the streamlined apartment living of the 1920s. Its restrained classical detailing, deep front porches, and balanced composition reflected the Davis Brothers’ taste for dignity over opulence. Though influenced by the Craftsman ethos of simplicity, the building also carried hints of Georgian and Colonial formality appropriate to Monument Avenue’s prestigious address.

Unlike speculative apartment rows in other cities, each Davis Brothers project — including the Seminole, Dorchester, and Greenwood Apartments — was slightly different. Variation in porch design, brick patterning, and interior proportions gave each structure individuality while maintaining a cohesive streetscape.

Life Inside, 1918

To live at 2812 Monument Avenue in 1918 was to occupy a space that felt both progressive and respectable. Tenants awoke to the hiss of the radiator and the smell of coffee brewing on a gas stove. Morning light filtered through lace curtains into parlors adorned with upright pianos and potted ferns. The day’s rhythm followed the city’s — office workers left by trolley, women shopped at the new department stores, children attended nearby schools.

In the evenings, residents returned home to tidy halls and the gentle hum of neighbors above and below. Dinner was prepared in the small but efficient kitchen — perhaps by a maid on Mondays or by the resident herself during the week. After supper, doors opened onto porches overlooking Monument Avenue, where the glow of gas lamps lit the magnolia-lined promenade.

These apartments symbolized freedom from domestic labor’s burdens yet retained the civility of home life. They were the architectural embodiment of a new social order — a world where comfort, propriety, and progress could coexist under one roof.

Legacy

More than a century later, the Seminole Apartments remain a testament to the Davis Brothers’ ability to merge craftsmanship, practicality, and social awareness. Their buildings were not palaces but well-built homes for an emerging class — solid, symmetrical, and enduring. At 2812 Monument Avenue, life in 1918 was modern, measured, and genteel — a glimpse into how Richmond learned to live upward, together, and with quiet grace.